Over the past eight months I’ve experienced life in a foreign country as it prepared for a presidential election, which ended on Sunday. Ecuador, like many of its Latin American neighbors, has a history of corrupt and authoritarian politics.

But they also share a history of strong revolutions and protests for what they believe in.

Voting is mandatory for literate citizens aged 18–59, and optional for 16–17 year olds. In a country with only about 5 percent the United States’ population, every voice matters so much more. Thus, the vote is mandatory and if you do not vote, you have to pay a hefty fine. It is also mandated that during the weekend of an election, starting Friday at noon, the country is dry, meaning that alcoholic beverages cannot be served, sold or consumed. This law is enforced against foreigners as well as a way to ensure that the election results depict an honest and sober opinion from the people. However, it doesn’t always go so smoothly or ethically.

The international students received emails about potential election and protest violence from the U.S. Embassy. We’ve seen our host families and Ecuadorian friends post about events planning to protest and block the streets in Quito.

On Sunday, Election Day, Ecuadorians cast their votes from all over the country for the candidate they believed should be their next president. The votes were counted and at 6 p.m. Guillermo Lasso, the right-wing bank owner who promised to cut taxes for big companies and create a million jobs through foreign investment, was the predicted winner, according to exit polls. But then there was a thirty-minute period where no vote information came in about the results. Then, when the results came back, Lenín Moreno, a left-wing populist, had taken the lead. It is now said that Moreno has won by only about four percentage points. A Moreno presidency would mean a continuation of Correa politics meaning polarized parties, censorship, high import taxes and alleged corruption.

Because of suspicious findings at some of the voting locations, and a push by Lasso and his supporters, the country is demanding a recount and that all ballots be checked for fraud.

On the Friday before the election, I boarded a bus for Cuenca, a city about eight hours from the capital Quito. There isn’t much to do on an eight-hour bus ride except stare out the window at the changing landscapes and get to know the countryside better. During the ride, I noticed how the political propaganda morphed depending on whether we were passing through the rural or urban areas. Urban areas, such as Quito, tended to be plastered in banners and flyers with Lasso’s face on it. Rural areas and small towns swayed more toward Moreno.

This surprised me because Lasso is a right-wing candidate and Moreno is a left-wing populist. This was a culture shock to me because typically in the United States, the cities with higher-educated people and millennials are where the liberals are found, while the rural areas are home to the conservatives. But here in Ecuador, and much of Latin America, it is the opposite. Millennials are supporting the right-wing, and the rural population is backing the left-wing.

How could that be when so many of the Lasso supporters I knew held to liberal ideologies?

A fellow student, finishing up her law degree, tells me that for the election she had to put her personal interests aside for the sake of change. Latin American governments have typically been socialist, with the exception of the military regimes (which the U.S. politically and financially supported out of the fear of communism). Despite believing in the ideologies of equality and a better future for all, these socialist governments haven’t had much success. Many have taken advantage of their power and have hurt more than they’ve helped.

“For me, now it is not a matter of supporting Lasso as if he were the savior of Ecuador, but the necessary change in politics to be able to enter another stage in Ecuador … as a woman, I find it very difficult to accept that I am supporting a candidate as conservative in matters as abortion. But I believe that all abuses of human rights, the criminalization of protest, the lack of freedom of expression, lack of economic freedom, corruption scandals, nepotism, etc., goes far beyond the conservative that Lasso would reach,” my friend told me.

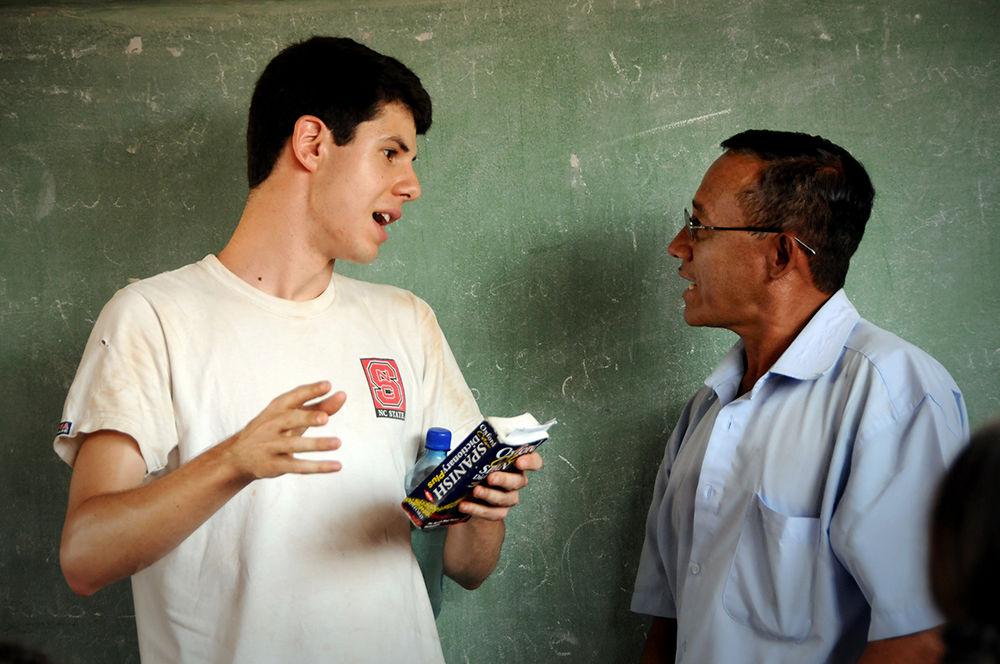

Wednesday, after the election, I walked to one of my classes and noticed a large commotion happening in the middle of the street. There were 50-plus students and other supporters protesting with signs that said things such as “respete mi voto” y “te luchamos o te perdimos” and flags that read “Lasso.” Unsure, I talked with a protester about why they were out there.

I’m both inspired and intrigued by the determination and outcry being heard from young people all over Ecuador over the results of this election. Although many of them do not wholeheartedly believe in the platform of conservative candidate Lasso, they’re determined to rid their country of corrupt politicians and bring freedom to their people.

Even if it means only having the choice of the lesser of two evils.