Despite many flounders over the years, NC State has made quite a few initiatives toward diversity and equity between all groups on campus. Between the campus community centers, the inclusion of diversity and equity policies in the classroom and how easy it is to get in contact with various students of different backgrounds on campus, it’s fairly easy to see that the NC State community is at least making an effort to be inclusive of all students on campus. But one diversity initiative that is often overlooked is language — particularly, discrimination over people’s accents and dialects.

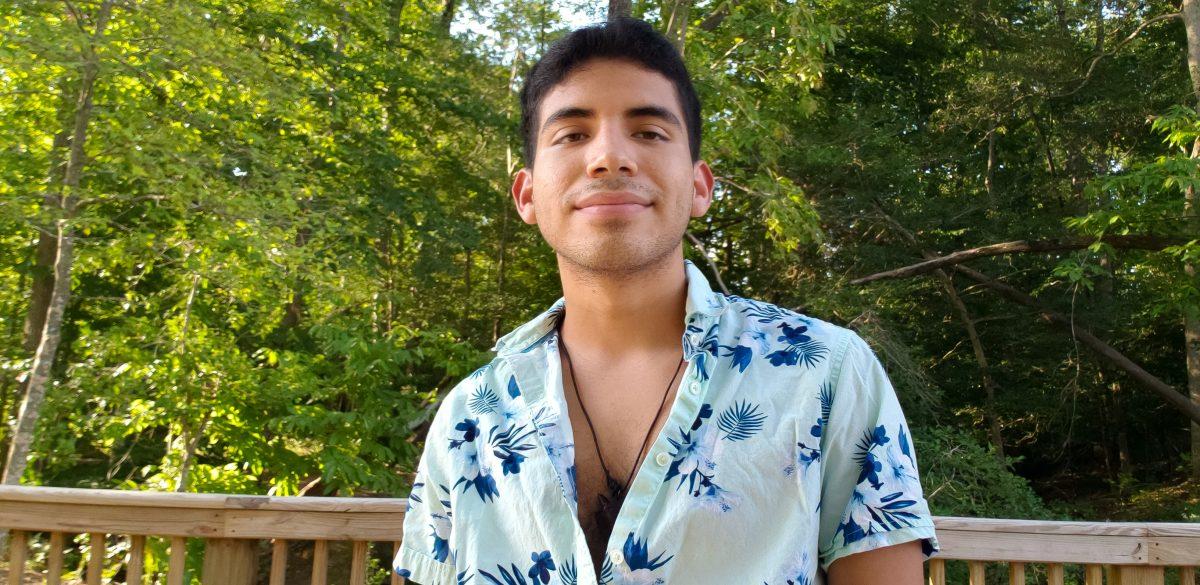

This semester alone, I had two professors immediately apologize for their accents, despite both speaking perfectly good and eloquent English, and both made this apology right at the beginning of first class. And while I understand the need to speak clearly towards students, I also wonder why so many students, staff and faculty feel pressured to apologize for seemingly nonexistent mistakes.

Professors are not the only people experiencing this problem. Countless times I’ve seen students worry about the way they sound towards their peers, from international students not being able to make friends because of their accents to American students worrying about how they sound in the classroom because of their Southern accents. It’s commonplace for many students, even if it’s not explicitly said. And you see these slights made in the academic sphere as well — in the humanities alone, many students and even professors will talk down on non-Western media and philosophies only by the way they are articulated, without even putting a glance into the actual content that is even said.

This is language subordination, a form of discrimination based on promoting certain speech dialects over others. In America, this often comes in the form of promoting a “standard” American English, one “without an accent” and that correctly follows “proper” grammar rules and regulations — both obvious misconceptions about how diverse American English is.

Through language subordination, a gateway is formed towards more overt forms of discrimination. Racism, for example, manifests through the invalidation of African American Vernacular English; xenophobia manifests through American students mocking the accents of foreign students, staff and faculty. It’s Southern students being worried that their accents will make them seem dumb, or gay men on campus putting up a “straight” voice to avoid discrimination in certain spaces.

There’s no clear answer to solving language subordination, either. In the United States, you can’t get far professionally without knowing the ins and outs of standard American English — indeed, language discrimination is a common issue in the workplace. So many international students, staff and faculty chastise their own accents and dialects, because NC State is an academic institution that primarily functions in standard American English, and expects most of its body to understand it.

But where does one draw the line between mastery and illiteracy, and who deserves educational, labor and social opportunities based on the way they speak? The answer to this question has a lot of weight, because it dictates who is allowed to thrive in the workplace, at school, or even at a social event. We’re talking about solving centuries of discrimination through language alone.

Acknowledging this issue is the first step. NC State’s linguistic department, for example, has a statement on language diversity and initiatives to discourage language subordination. Other university departments should look into these initiatives and apply them, because the linguistic department is not the only department on campus with a variety of dialects and accents.

Lastly, students can also take their own initiatives to fight against language subordination. Every mock and slight towards someone’s dialect or accent should not be tolerated; instead, NC State students should be proud of the linguistic diversity found on campus and call out these slights for what they are: acts of discrimination. I promise you, your impression of your foreign professor’s accent is not funny.