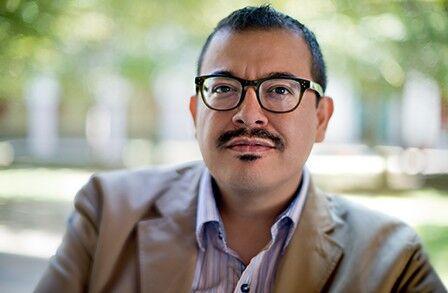

The Lambda Literary Foundation recently awarded Eduardo Corral, an assistant professor in the Department of English, a Lambda Literary Award in the category of Gay Poetry for his second collection of poems, “Guillotine.” A self-described “slow writer,” Corral centered themes of the Mexican-American borderlands and queerness in the collection.

“The key to understanding ‘Guillotine’ is the title: the cut, the separation,” Corral said. “At the level of immigration narratives, moving from one country to another — you’re cut off from one country as you enter another country.”

Corral has received several accolades and fellowships throughout his career, but he never takes too long to celebrate his accomplishments. Rather, he chooses to celebrate for a few days at most and move on, striving to avoid internalizing both the achievements and disappointments.

Although Corral’s first collection of poems, “Slow Lightning,” truly kick-started his career as a nationally acclaimed poet, he strove to spark the same incredulity and astonishment within readers.

“The first book was a very important book for me because it made a career in poetry possible,” Corral said. “And the second book just kinda reminded people — ‘Oh, here he is again, [writing] about the border and queerness but he’s still, hopefully, surprising us.’ That’s the one thing you want out of poetry. Delight, surprise.”

The annual Lambda Literary Awards, announced on June 1, 2021 to kick off Pride Month, honor published works that explore LGBTQ themes. According to Corral, centering queerness in his work was crucial amongst other themes such as immigration and the borderlands.

“That’s very important to me, as a gay man, to write about queerness,” Corral said. “That’s one of the things I tried to do with the first book, to… ‘queer’ border narratives. To actually have gay men and women moving through the borderlands, which I never saw before.”

At NC State, Corral is a faculty member of the MFA creative writing program and teaches poetry for graduate students. He also runs graduate-level workshops and leads seminars on contemporary American poetry.

“It’s a great experience as a teacher, because my favorite part about being a teacher is that each new crop of students, each new cohort refreshes my own interest in the language and the craft,” Corral said. “They ask questions I haven’t thought of before. Their questions recharge me, and they bring new work to me.”

Despite his success in the realms of academics and poetry, Corral claims he became a poet “quite frankly, by accident.” A Mexican-American literature course at his alma mater, Arizona State University, offered a poetry workshop in the middle of the semester, much to Corral’s chagrin at the time.

“I was about to drop that course, but I kept it because — the only reason I kept it was because it met twice a week at 2 p.m., and I’m not a big morning person at all,” Corral said. “I said, do this one class, you’ll find a way to make the poetry thing work.”

Corral discovered his love for poetry through the late Derek Walcott, a Saint Lucian poet and playwright who received the 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature. One of his professors at Arizona State recommended Walcott among a list of other established 20th-century poets such as Rita Dove and Lorna Dee Cervantes.

“I walked away from [Walcott’s] book just delighted, and a second thing happened right after that: audacity set in,” Corral said. “First, I was inspired by these wonderful writers, then audacity set in. ‘What can I do?’”

Another reason Corral originally never saw himself as a poet was because of his struggles with dyslexia. However, his tendency to slow down a sentence word by word to comprehend the syllables and make sense of them proved quite useful in the process of writing poetry.

In fact, Corral noted that students across the board use poetic language daily, through tweets, abbreviations and the like.

“The way you play with and corrupt language with abbreviations, new coinages,” Corral said. “The way you use emoticons and images to equal or relate an emotional, intellectual state — what’s going on. That’s imagery, that’s the basis of poetry.”

As a piece of advice to aspiring writers and poets, Corral suggests that they not only listen to the stories being told around them, however mundane or exciting they may be, but to also pay attention to how those stories are told.

“I started listening to not only what was being said, but how it was being said,” Corral said. “How the story was being narrated to me. Was it jokey, was it serious, ending on a different tone? I listened to the way a story or a joke or an antidote was told to me. That made the difference, because it helped me realize I can vary the way something was said on the page.”