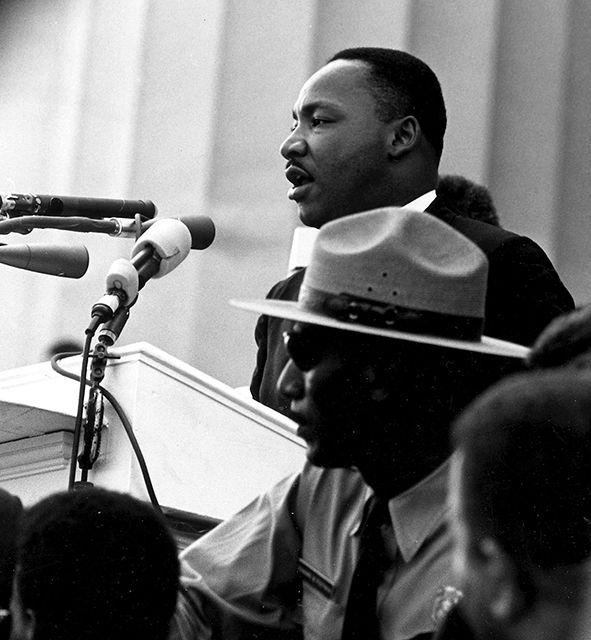

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his gripping “I Have A Dream” speech. Until recently, it was unknown that King’s speech debuted on North Carolina soil. Prior to the March on Washington, those same words echoed inside a segregated high school gymnasium. Unbeknown to historians, the recording was tucked away in a library in the small town of Rocky Mount.

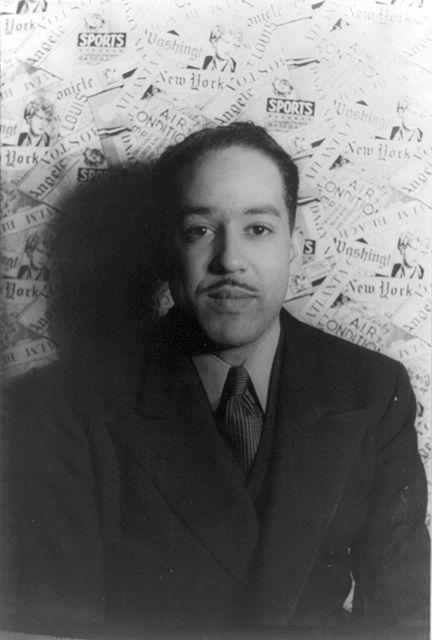

NC State English professor Jason Miller’s extensive research for his book “Langston Hughes and American Lynching Culture” catalyzed the discovery. It was then Miller suspected that King referenced Hughes’ poems in his speeches. Strolling through the aisles in the D.H. Hill Library, Miller picked up the “Trumpet of Conscience” book by King.

“After flipping through the pages, I came to a sermon that said, ‘I have personally been the victim of deferred dreams,’” Miller said. “‘Deferred Dreams’ is one of Hughes’ most popular poems.”

Miller found that King used seven different Hughes poems in his sermons and speeches. The two men met, frequently exchanged letters, and King had once requested Hughes to write a poem in tribute to A. Philip Randolph, a civil rights activist. The central theme of the poem was Randolph’s profound ability to dream, which helped King view dreams in a positive light. According to Miller, it wasn’t until the 1960s that he viewed dreams as optimistic and inspirational.

“It’s really shocking to people, but when King first started talking about dreams in 1959, he talked about them in a negative way, as in shattered dreams and blasted hopes,” Miller said. “That was a very unusual thing to discover.”

Miller’s “Origins of the Dream” shares how King’s dream is traced to Hughes’ poetry. The book reveals that King wasn’t just a preacher or political figure, but also had the persona of a poet. According to Miller, some of King’s earlier speeches were rhythmic and written in poetic meter.

“The overarching theme was that this was a moment when poetry and politics went hand in hand,” Miller said. “What makes Dr. King’s ‘I Have A Dream’ so memorable is the poetic element of it — the repetition, metaphor and the way it’s enunciated.”

Dedicated to his research, Miller traced every intersection between King and Hughes. Near the end of his research, he found that King once spoke in Rocky Mount.

“I have this gigantic timeline, which is 14 feet long and 3 feet high. It has five different colors on it,” Miller said. “If they shared letters, I’d mark it down.”

Miller eventually located a transcript, though it was plagued with question marks and ambiguous text. An exhaustive search led him to the Braswell Memorial Library in Rocky Mount. Nestled in a rusted box was the reel, marked in pencil “Dr. Martin Luther King speech — please do not erase.”

“The reel was cracked, and the end of the tape was dangling, curled and bent,” Miller said. “It stirs up your greatest hopes and your greatest fears; it’s very rare when all of your greatest hopes are realized and your greatest fears are annulled.”

The tape was hand-delivered to George Blood in Philadelphia, whose expertise digitized and restored the speech.

“It really did take a CSI level of reverberation and skill,” Miller said. “It was like the archaeology of the human voice, scraping away the dirt and the dust and bringing it back to life.”

According to Miller, people incorrectly refer to the speech as a rough draft, when in actuality the delivery is the fullest expression of the dream. During the March on Washington, King adds “I Have A Dream” to the end of his speech, whereas it’s thematically and organizationally mentioned in Rocky Mount.

“It really shows the whole trajectory of what the speech was moving toward and what it became,” Miller said. “It’s fuller, more contextual and more dramatic, but obviously what’s not there is the irreplaceable moments of history that happened at the March on Washington.”

The Rocky Mount rendition includes the iconic endings, “Let freedom ring,” “How long, not long” and “I have a dream.”

“I’ve listened to about 150 different sermons and speeches, read transcripts of about 700, and I’ve never heard all three of his most important endings in one place,” Miller said. “It really is Dr. King’s greatest hits.”

Miller spoke with original attendees of the speech, a few of which will be interviewed for the upcoming documentary, “The Origin of the Dream.”

“Their stories are amazing,” Miller said. “I’m still shocked to this day how attending a speech has become a turning point in so many people’s lives, driving them to a life of civil service, social responsibility and an active endeavor in trying to make the world a better place.”

According to the documentary’s director, Rebecca Cerese, it will be a mix of archival footage, animation, dramatic readings and audio. The documentary will also feature interviews, including civil rights activists Julian Bond and Andrew Young. The film will address how Hughes and King crossed paths.

“It’s an amazing opportunity to add to the historical record of these two cultural icons,” Cerese said.

A clip of the documentary will be presented at the August event, “Experiencing King,” at NC State. Several distinguished guests are invited, including artist Synthia Saint James, who did an original painting for the film, and actor Danny Glover, who will perform as Langston Hughes in Stewart Theatre.

Currently, Miller is on the road for his 14-city book tour. Last week at Flyleaf Books in Chapel Hill, he encountered an unlikely visitor: the son of the pastor who invited King to speak in Rocky Mount.

“His dad and King grew up in the same neighborhood and appeared at the same exercises,” Miller said. “We keep learning and gathering as we go; the project keeps evolving and growing at every stop along the way.”

“What makes Dr. King’s ‘I Have A Dream’ so memorable is the poetic element of it — the repetition, metaphor and the way it’s enunciated.”