James B. Hunt Jr. Library is the scene of some interesting happenings these days. This weekend, it will host the North Carolina Literary Festival. The theme of this year’s conference is “The Future of Reading.” Along with engaging with traditional forms of reading and literature, the festival will also “explore the new, often technology-based ways readers are encountering, experiencing and interacting with literature.”

On the festival’s website, Hunt Library has been described as having “generated international attention for its stunning modern architecture, its ubiquitous technologies and its many simulation and large-scale visualization rooms.” The library is meant to be a centerpiece of the festival by “inspiring conversations about the future of reading and reading-based technologies.”

Ironically, these same days, on entering this lauded library, one can see a donation box reading “Help Support Hunt.” A student campaign (www.savehuntlibrary.com) is currently underway to prevent Hunt Library’s hours from being cut, due to the $1.3 million (5 percent) budget cuts this year to the NCSU Libraries. As of March 27, more than 5,000 students, equivalent to about 16 percent of N.C. State’s entire student body, had signed the petition to prevent having the library close on weeknights at 11 p.m.

Now, the only proposed cut in hours to D.H. Hill Library is for Sunday night. What could be the reason that it’s the acclaimed Hunt Library that’s facing cuts and not D.H. Hill?

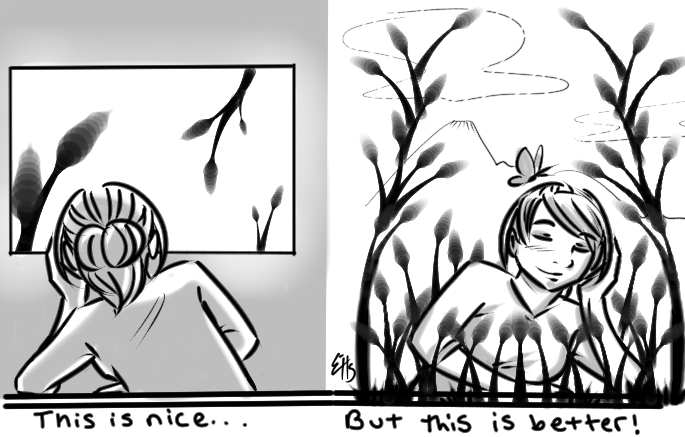

Both Hunt’s acclaim and predicament stem from the same reason. Hunt Library was only ever meant to be a spectacle, something that put N.C. State on the map. More than just a library, it was meant to be the place where N.C. State could host literary festivals, and people could be awed by it. And these kinds of attention-getting events and people only come during the daytime. D.H. Hill, on the other hand, never lost its function of being a library, rather than being a futuristic glass spawn of a battering ram and the Dorton Arena.

So it’s Hunt whose hours are being cut, and many students don’t want that to happen. Though it’s beautiful to see students come together to rally for a cause, the precise reason as to why students don’t want Hunt’s hours to be cut should be examined.

On the surface, it’s clear—and true—that cutting library hours will, to some small or significant extent, affect students’ studying. Save Hunt Library’s homepage says the purpose of the campaign is “to keep both libraries at N.C. State adequately funded such that the academic endeavors of all students are not inhibited.” But that begs the question, why are academic endeavors important? For finding jobs or for learning? Neither answer would be true for all students, nor can I speak for all students, but I suspect that more students care about their education as a means to a career. We rally for Hunt Library to stay open, but only because we fear that our GPAs may fall if it doesn’t.

But in the backdrop of the Literature Festival, a third possibility for looking at learning and its artifacts arises, beyond learning being regarded as a process with value in itself, or “learning” as a means to money. Besides Hunt Library itself, anything happening at Hunt, by virtue of its context, is to some extent a spectacle. This includes the Festival. And with that, naturally, also the subject of the Festival: literature.

Which brings up the final question: If the greatest interest of the University, both in terms of prestige, and following that, financially, lies in turning literature into a spectacle—and universalizing literature, turning learning, intellectualism, culture, etc. into a spectacle—then isn’t the struggle over Hunt Library fundamentally a form of class struggle? On one side, there’s the administration, seeking to create profit through making a spectacle of culture and intellectualism and cutting back on aspects that don’t lead to profit. On the other side is the student body, manifesting its material aspirations through turning culture and intellectualism into means of mobility.

Literature festivals may be small sparks of genuine engagement with culture, but let us not forget that behind their cover, profound economic battles are raging. And until those battles are resolved, such festivals will only constitute cultural events, rather than representing culture living autonomously of the workings of capital.