On Jan. 1, The New York Times and The Guardian published editorials urging President Barack Obama to grant Edward Snowden clemency. Snowden is the whistleblower responsible for the leaks, which took place in June, regarding the NSA surveillance program PRISM, and he is currently in political asylum in Russia. Since the he leaked the information, his portrayal from the security establishment has been hostile, and government officials from the United States have been trying to get their hands on him to try him for treason

In light of this, such a step taken by mainstream publications not just lauding his actions, but also pressing Obama to grant him safe passage home is rather special and, it could well be argued, impressive. It is one thing, in an editorial, to take a stance about an issue; it is quite another to phrase the rhetoric as telling the President what to do. Some might look at this happening and see such media groups as the heroes we’ve been waiting for. But one of the first questions that people should be asking themselves is, “Can news outlets, however influential, pressure the state to change?”

The answer is no.

Granting clemency to Edward Snowden would amount to the government voluntarily relinquishing control over a focal point in the battle between it and the forces that are against its power. But the U.S. government (or any government in an equivalent position), being the entity it is, would never do that.

Actions of power at a structural or societal level are fundamentally driven by economic logic, not moral motives. And the benefits about the power nexus integrating the government (executive branch, NSA, etc.) and the private sector (the contractors whose business is the defense/intelligence complex) have taken form and been normalized in such a way that the economic flow into a tiny cluster of points is too great for this power nexus to give it up when simply asked to. Power must be wrested from the existing structure and dispersed more democratically, or in other terms, more anarchically. In other words, the power structure must be destroyed. Having come to the point it’s already at, that is the only way it will stop accumulating and abusing power as it is.

To bring it back to Snowden, the U.S. security establishment has vested interests, interests essential to its very existence as it is, that would prevent it from backing off in the slightest in going after Snowden. It is intrinsic to the nature of power to want to surveil, and it is intrinsic to the nature of a lot of power to want to surveil a lot more. And because the security complex spying on us is a case of “a lot of power,” whistleblowers like Snowden are a threat to its hegemony, and it’s not going to pardon whistleblowers unless forced to. [This is empirically true for the U.S.: the power of the U.S. as a national entity, and with that, the power of security establishment, have grown exponentially since 9/11, and as would be expected in that kind of situation, Obama has prosecuted more than twice as many whistleblowers (seven) under the 1917 Espionage Act than all prior presidents since then combined.]

Frederick Douglass was correct when he said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” The exhortations of newspapers can be demands, but U.S.-government-exhorting newspapers are as much constituents of the U.S. government as citizens of other countries are. They can only force the U.S. government to do something if other such external agents can threaten the government with negative consequences, which publications by themselves cannot do. Or, they can only force it if its own constituents want something to happen as well, which is what will be required here.

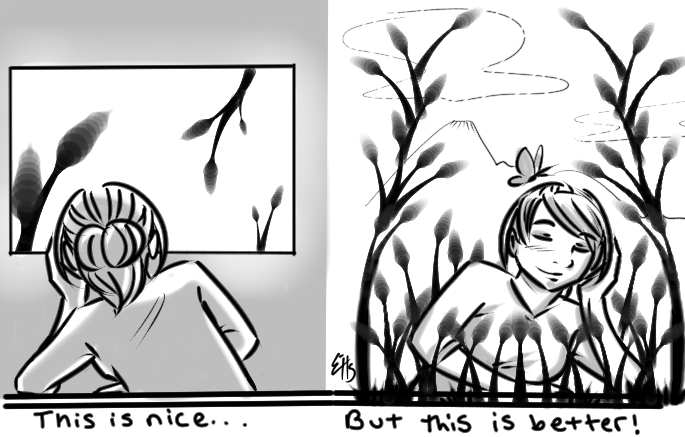

Looking at it structurally and objectively, The New York Times and The Guardian writing editorials asking the bitter winter to grant us clemency has as much power by itself to make the weather warmer as does this enjoinment to Obama. But that’s not going to happen. Reality is already at a certain point, and that’s what we have to work with, not a simpler, easier one that we wish we were in — be that the reality of power structures or the reality of climate change. Cases of assertion like these from The New York Times and The Guardian are boosts that we can use, but in the end, newspapers just print words, while people transform reality.