Known for its tall windows and abundance of bricks, most NC State students have passed through Tompkins Hall for English 101 at the absolute minimum. From its origins resembling a textile mill to its destruction from a devastating fire and its current role as the home of the English department, the building has been a silent narrator of the University’s evolving history.

Tompkins Hall was originally built in 1902 and was simply known as the “Textile Building” for its first decade and a half on campus. The building was originally funded by $10,000 from the North Carolina General Assembly which was lobbied for by Daniel Augustus Tompkins, who designed the building and did similar work for Clemson University.

Tim Peeler, a writer and editor for University Communications, said the building was originally designed to look like a cotton mill.

The need for such a facility arose in 1899 when the textiles program became an official part of the University. Peeler said Richard Stanhope Pullen, who donated the initial land for NC State, required that a cotton gin be built on any land he gifted, “because textiles were the way of the first industrial complex in North Carolina’s history.”

The building’s tall, wide windows, especially on the upper floors, were designed to dry dyes and provide ventilation for the $25,000 worth of machinery donated by textile companies.

“Because machinery is very hot and you just had to have some sort of ventilation in a time long before air conditioning was invented,” Peeler said.

The original building included a tower, on which graduating class numbers, baseball and football scores were painted on.

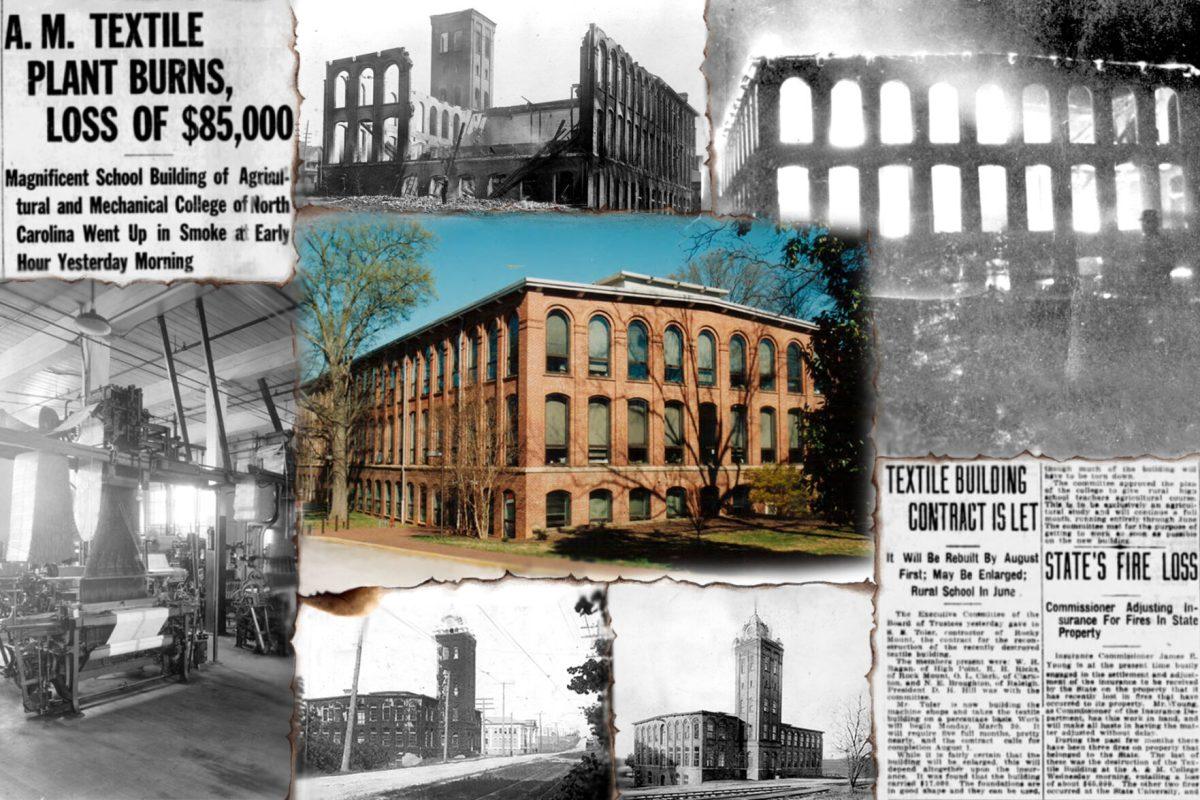

However, Tompkins Hall’s early history was marked by tragedy. A fire almost entirely destroyed the building in the early hours of March 25, 1914. The origin of the fire remains undetermined.

The News & Observer reported that students aided in attempting to put the fire out, using three lines of hose and a college water tank.

“In bathrobes and bedroom slippers they manned hose lines and crept up within the breath of the flames and turned on what feeble streams were at the command of the depleted mains,” the News & Observer reported. “The other students looked on with an expression almost heartrending.”

The News & Observer described the incident as an “awe inspiring spectacle.”

“With the tall tower, a mass of red tongues to its very top, standing like a beacon over the campus, the sight was indeed a spectacular one,” the News & Observer reported.

The burning caused the University to suffer $85,000 in losses according to the News & Observer, which equates to approximately $2.7 million today.

The University quickly responded to rebuild the Textiles Building, with the first wing receiving funding in 1915. In 1918, it was named Tompkins Hall for Daniel Augustus Tompkins’ contributions to the department. However, Tompkins was known for pushing negative views of Black people and their integration into the workforce.

“It would seem impossible to work a force of mixed white and black labor where white women and negro men would be … co-workers,” Tompkins wrote in the 1899 “Cotton Mill, Commercial Features” textbook. Tompkins continued that it was “doubtful whether [African Americans] can ever be successfully used as cotton mill operatives … except in the more menial occupations.”

Following the building’s reconstruction, the Textile Department returned, remaining until 1938 when it moved to Nelson Hall. Afterward, from 1939 to 1980, the building housed a variety of departments, including education, mathematics, liberal arts, politics and speech.

“Technician offices were in Tompkins at one time, a whole lot of different things,” Peeler said.

The most significant transformation from this period occurred in 1981 when the English Department moved into Tompkins Hall following a $5 million renovation. This renovation also included the construction of a link between Tompkins and Winston Halls, aptly named “Link” at the time, but was eventually renamed Caldwell Hall after Chancellor John Tyler Caldwell.

Peeler said the construction of Caldwell Hall aimed to create a more cohesive and aesthetically pleasing campus environment in an area where buildings were planned and built decades apart — as Winston Hall and Tompkins Hall aren’t level with each other.

“Caldwell was built to expand the programs,” Peeler said. “And the buildings don’t exactly match up, so that’s why it’s so oddly shaped and there’s the ramps and the stairs and all the things in between. It is because they were not originally built to be linked in that way.”

Tom Stafford, a former vice chancellor of student affairs who attended NC State’s graduate school in the 1960s, said Tompkins is generally underappreciated for its location on Hillsborough Street and for most students using the building’s less scenic back entrance.

“Unfortunately, it is located in a place on the campus that lots of people go through, go up and down the front of it, and they go up and down the back side of the building,” Stafford said. “… They hardly ever get a good view of what it looks like because it’s sort of hidden, almost even though it was right on the edge of Hillsborough Street.”

One aspect of Tompkins Hall’s enduring legacy is its universality — not only to humanities majors but to all students.

“I would say that at one point or another, most likely in the freshman year, every incoming freshman at NC State goes in and out of that building,” Stafford said. “So on that point alone, you can say it’s a really ubiquitous building.”

Having stood over a century, Tompkins Hall is more than just bricks and mortar; it’s a living, breathing piece of NC State’s story. Whether it be an English major dissecting Shakespeare or an engineering student fulfilling a core English requirement, Tompkins Hall connects students to generations of students who have come before.