Few artists aspire toward the poeticism which Sufjan Stevens exhibits consistently in his work. If you strip bare the lyrics, separating them from their musical arrangements and Stevens’ vocals, they stand on their own, detailing a story.

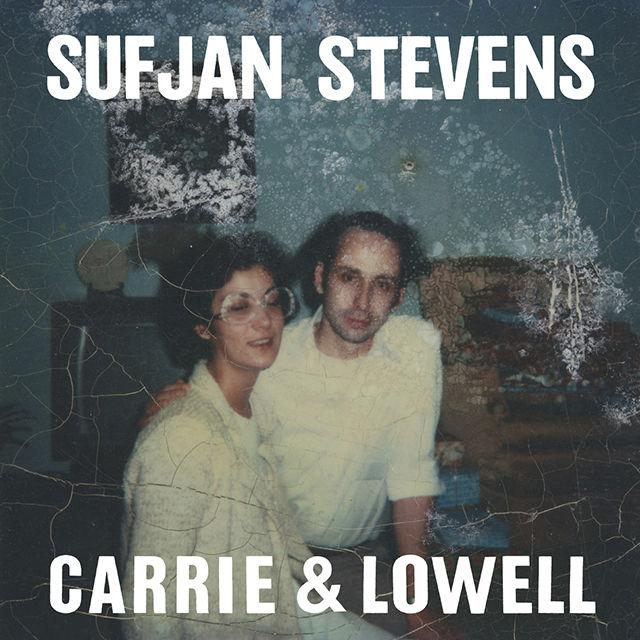

The title of Stevens’ newest album, “Carrie & Lowell,” refers to the artist’s mother and stepfather, thus marking the intimate nature of his latest work. He longs for the past, and he is afraid of death. This is indicated eloquently through lines such as, “What’s left is only bittersweet / For the rest of my life, admitting the best is behind me.”

This intimacy is unadulterated, and this, at times, means that the album is difficult to listen to. The album is better for it.

It’s refreshing to see an artist address death without that snippy, nihilistic self-awareness that we commonly see nowadays (see Kesha’s “Die Young,” or Foster the People’s “Pumped Up Kicks”). Instead, when Stevens speaks bluntly about death, he is sad. He has difficulty coming to terms with it, a fact indicated by his refrains of, “We’re all gonna die,” in the track, “Fourth of July.”

He contrasts the bright ideals of the American dream with harsh truths that distract him from enjoying the party. Stevens doesn’t intend to paint broad, moralizing strokes regarding the current condition of the United States. Instead he wants to show his raw wounds and how they are healing.

Stevens has in his more recent albums tended toward objective experimentation, a propensity that summoned a distance between himself and his audience. With “Carrie & Lowell,” he revisits what he initially became known for—his personal inclinations, elegant lyricism and beautifully simple arrangements. And what perhaps makes this album his best yet is his perfect, unflinching honesty.

In most of his songs here, Stevens deftly lays out structures, allowing his songs to finish as predicted. At least, until the songs reach their ending, at which point some tracks veer into unexpected, unique territory.

The first song, “Death with Dignity” (a fitting opening track for an album so focused on death), maintains the last words, “You’ll never see us again.” However, with these words, the song is hardly done. They lead into 40 seconds of graceful, almost orchestral instrumentation.

The best song of “Carrie & Lowell” is “John My Beloved,” a wonderful practice in restraint. Stevens’ vocals take priority here, and they are quiet, tense and controlled. Of course, Stevens has always been one to lean away from showy vocals, opting instead to be a vehicle for his music and lyrics.

This is not to say that anyone could sing these songs. Part of the beauty of the album in its entirety is that it could only be Stevens’, as it relies inherently on his personal narrative.

“Carrie & Lowell” is enhanced by a lingering darkness—the presence of imminent death that Stevens himself can no longer ignore at this point in his life. He touches on the theme, pulls back as though afraid and then lurches headfirst into confrontation, into desperate endeavors to find something to latch onto.

In his anxiety he says, “I’ll drive that stake through the center of my heart / Lonely vampire inhaling its fire / I’m chasing the dragon too far.” Here, Stevens fluidly pulls together the themes of the album: his discomfort with death, his intense desire to escape his circumstances and his longing for a past he cannot revisit.

Sufjan Stevens has constructed an album that explores such ideas with poise and fervor.